Although filmmakers began producing LGBTQ films to promote gender equality, they still continue to misrepresent queer portrayal in certain ways. By maintaining the heteronormativity in the film, mainstream cinema excessively utilized the male gaze to make straight viewers feel comfortable and safe. Here, the gender identities have been removed from the film, as well as the lived experience of LGBTQ people; this also includes gender oppression and the minority stress in the LGBTQ community. As a result, Hollywood films use media aesthetics to oppress those who identify as LGBTQ by asserting heterosexual pride within LGBTQ cinema. With this disruptive pattern in Hollywood films, the audience will never acknowledge the actual content of LGBTQ people and the traumatic experiences the community consistently faces. On the other hand, the historical drama film, Portrait of a Lady on Fire (2019) by Céline Sciamma represents the aspect of LGBTQ characters differently from mainstream cinema. In this paper, I will analyze how mainstream cinema misrepresents LGBTQ people and takes away their cultural value through the male gaze.

According to the depiction of LGBTQ characters, mainstream cinema frequently uses the stereotypical image of LGBTQ people to satisfy the heterosexual audience. By repeating the disruptive narrative strategies, the film does not provide enough cultural representation and eliminates the expression of queer identity in the film. As Cáel M. Keegan pinpoints this issue in the article, History, Disrupted: The Aesthetic Gentrification of Queer and Trans Cinema, “queer and trans people ourselves have become almost entirely absent, gentrified out of our own history by those who benefit from representing us—to themselves,” (Keegan 51). Here, it is obvious that the capitalist system has heavily affected the LGBTQ community, as they try to sustain gender normativity through films and distort the personal stories of LGBTQ people. To add, most of the queer films are directed by a straight white male and rarely allow the LGBTQ community to represent their identities. Instead of allowing the transgender actors to portray the direct experience of LGBTQ people in queer cinema, the industry chooses straight and cisgender actors to portray the trans characters and adapt the script to fit the concept of heteronormativity. This explicitly shows how the big business has extremely exploited the queer characters to provide heterosexual viewers with the feeling of “safety.” In the same way, they merely focus on the profits without acknowledging the true stories of LGBTQ people: “LGBTQ film roles are written for straight and cisgender (i.e. non-transgender) actors who might win awards, while queer and transgender actors struggle to get work,” (Keegan 51). With the exclusion of LGBTQ actors, mainstream cinema removes the queer content and replaces the realistic image of LGBTQ people with the substituted form of heteronormative idealization.

In contrast to the disruptive narratives, this historical film, Portrait of a Lady on Fire, illustrates the fidelity of queer characters through the lesbian gaze. Céline Sciamma, the director of the film, used media aesthetics to tackle the issues of gender roles in the male-dominated society. Not only does Sciamma identify as a lesbian herself, but Adèle Haenel, the main character of the film, is also a lesbian actress who promotes LGBTQ pride. Therefore, this film is able to preserve the queer narratives by the inclusion of a lesbian actor, as well as breaking the norm of heteronormativity through the LGBTQ lens. In the film, Sciamma puts women in the centre while the viewers will only see the male characters in the first and ending sequence. The absence of men allows the audience to focus on the female perception and the character growth (Abraham). Unlike mainstream cinema, the film does not try to assert the straight male characters and sex scenes to attract the heterosexual audience. As Jonathan Petrychyn criticized queer movies in the mainstream, “This post-New Queer Cinema, affected by television networks that "delivered its cuddlier versions" of New Queer Cinema to the masses in the early 2000s-think Will and Grace or Queer Eye for the Straight Eye-often err toward happy endings and homonormative representations.” Here, it is evident that mainstream cinema excessively relies on the heteronormative system to portray the LGBTQ characters and exclude the queer narratives. Through the lesbian gaze, Sciamma certainly owns her narrative and agency to depict the faithful context of queer characters.

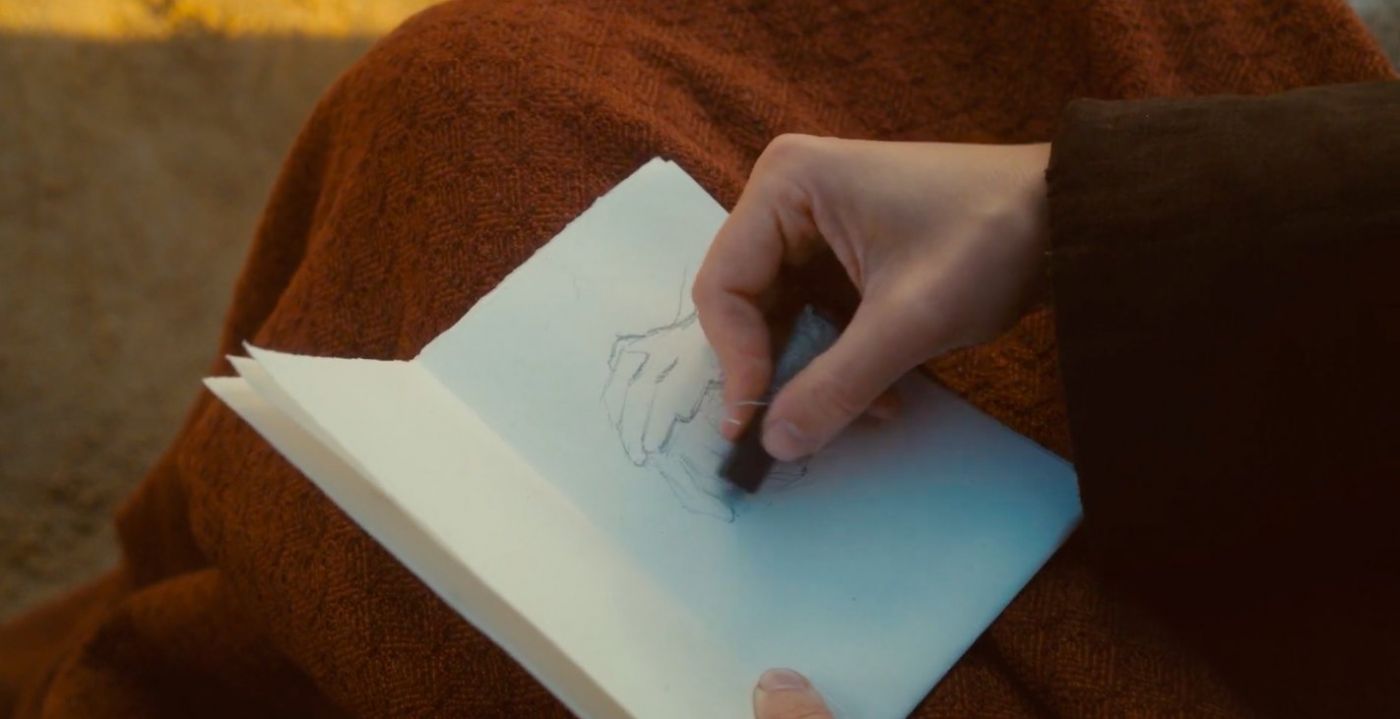

Instead of portraying the characters’ intimacy through touching, Portrait of a Lady on Fire combines the power of art and the female gaze together to create emotional tension. This art of looking can be tied to Foucault’s aspect of media representation, as he pinpoints that the well-made medium will be able to construct the value and represent the reality itself: “it doesn’t make its way around any obstacle, it is not distorting any perspective, it is addressing itself to what is invisible both because of the picture’s structure and because of its existence as painting” (Foucault 8). Despite the fact that some media elements may be invisible to the viewers, the film is able to reveal the hidden message itself. In addition, Foucault also used the artwork as a metaphor to express how the audience can perceive the media aesthetic through their sensation. By looking at pictures from a distance, the medium can create pleasure and construct the meaning related to space and the object. For this reason, Sciamma implied the massive use of the female gaze as a way of building up the emotional intensity. For instance, Marianne had to secretly observe Heloïse and memorized her gesture in order to paint a perfect portrait. At the same time, Heloïse also looked at Marianne while painting her from the model’s position (Tapponi). The interplay between the model’s position and the painter’s gaze indeed creates pleasure and a sense of mystery to the audience, as if they are looking at the painting in the gallery—the picture is beautiful and breathtaking; however, they cannot touch it. Sciamma visualizes this different position to portray the social hierarchy and the forbidden love between lesbian characters.

In terms of preserving cultural value, the film also traces the viewers back to the eighteenth century, where women were trained as professional artists. However, women were not allowed to join the public activities, as they were expected to get married and take care of the household. As a result of the fact that women held a lower social position compared to men, they are assumed to be weak and lacking in intellectual capacities: “Rather, the feminine is the signification of lack, signified by the Symbolic, a set of differentiating linguistic rules that effectively create sexual difference.” (Butler 37). In the film, Sciamma is able to tackle the issue of gender roles without inserting the male characters in the frame. This explicitly shows how Sciamma uses the medium to represent the female position in the patriarchal structure. For example, Marianne was able to establish her own exhibition because of her father’s name. Hence, she did not get any credits for her own artwork. Additionally, Sciamma also taps the insight view of abortion to the point where women are strong enough to hold the pain, and they should be admired for this, rather than having their actions perceived as a sin or malicious intent.

Through the lesbian gaze, Sciamma used the film as a way of resisting the heteronormative structure and pointed out the true identity of LGBTQ people. This notion can be related to Bell Hooks’ concept of the oppositional gaze, where the viewers can find comfort in mainstream cinema that misrepresents the LGBTQ community. Hooks noted that mainstream cinema rarely acknowledges gender issues and reproduces the film that contains the idea of racism and sexism, which also includes the portrayal of characters and the dialogue used in the film (231). Moreover, most of the filmmakers also depict the female character as a "sexual object." Nevertheless, Sciamma’s portrayal of individuals who identify as lesbian is able to represent both female and queer identities without repeating the male-dominated structure.

Works Cited

Abraham, Raphael. "Céline Sciamma on Defying Convention with the all-Female Portrait of a Lady on Fire." FT.Com, 2020. ProQuest, http://ezproxy.lib.ryerson.ca/login?url=https://www-proquest-com.ezproxy.lib.ryerson.ca/trade-journals/céline-sciamma-on-defying-convention-with-all/docview/2355127204/se-2?accountid=13631.

Butler, Judith. "Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity". Routledge, 1999;2011;, doi:10.4324/9780203824979.

Foucault, Michel. "The Order of Things". Taylor & Francis, 2012.

Hooks, Bell. "the Oppositional Gaze Black Female Spectators." Routledge, 2015.

Keegan, Cael M. "History, Disrupted: The Aesthetic Gentrification of Queer and Trans Cinema." Social Alternatives, vol. 35, no. 3, 2016, pp. 50-56.

Petrychyn, Jonathan. "film Festivals in the White Cube: Queer City Cinema as Artistic Practice." Canadian Journal of Film Studies, vol. 27, no. 1, 2018, pp. 59-72.

Tapponi, Róisín. “It’s about Time Film Began Representing the Lesbian Gaze.” The Guardian, 11 Dec. 2020, www.theguardian.com/film/2020/feb/28/its-about-time-film-began-representing-the-lesbian-gaze-portrait-of-a-lady-on-fire.

เข้าสู่ระบบเพื่อแสดงความคิดเห็น

Log in